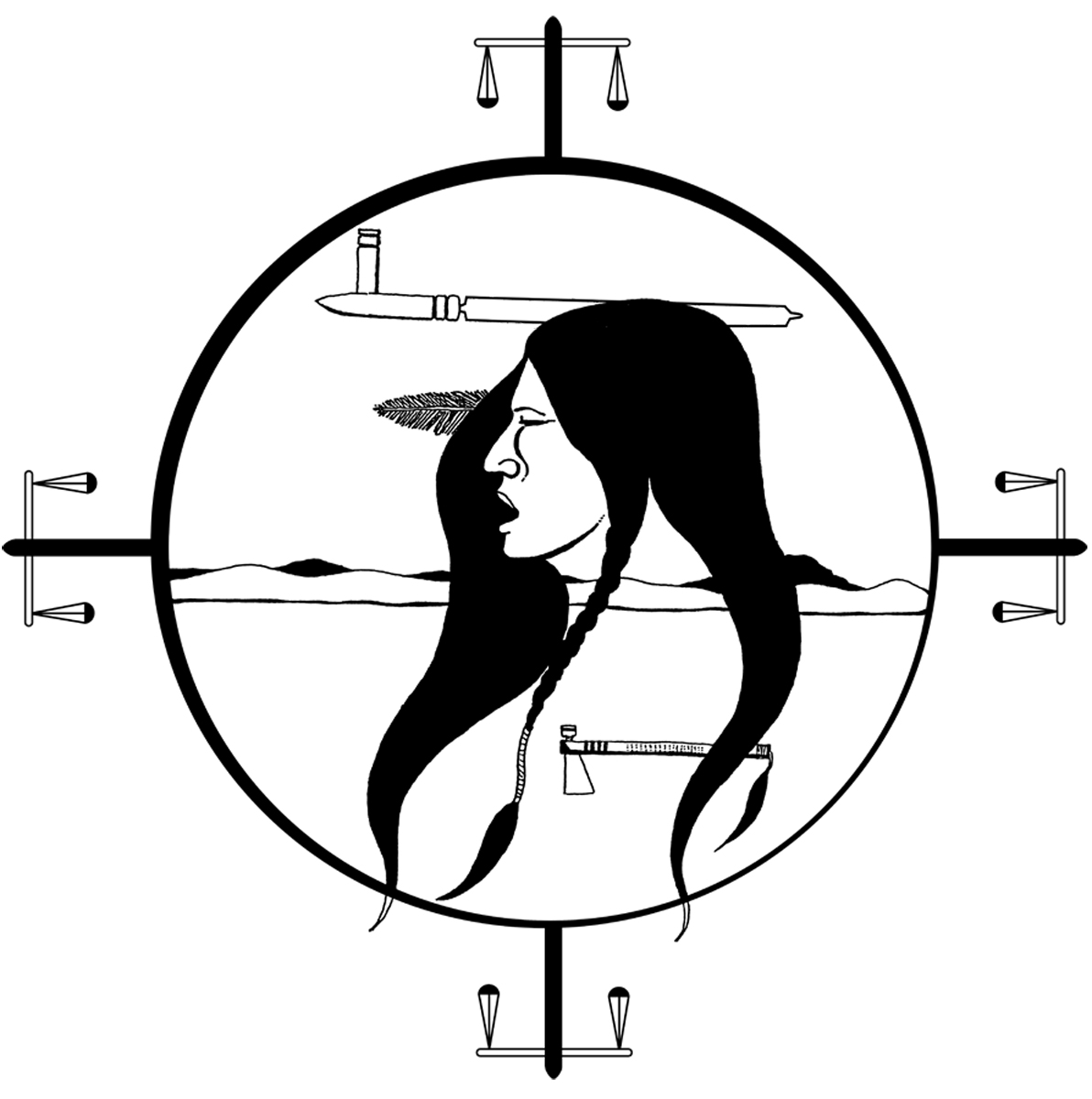

Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc Indian Band v Canada

The Federal Court released a decision on June 3, 2015 in Tk’emlúps te <a href="http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/fct/doc/2015/2015fc706/2015fc706.html" title="Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc Indian Band v. Canada"><i>Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc Indian Band</i> <i>v. Canada </i></a>, certifying a class action proceeding against the federal government on behalf of day students who attended the Indian residential schools covered by the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (“IRSSA”), as well as their first generation descendants and the Indian Act bands that had residential schools operated on their lands.

Background

The IRSSA has provided some compensation to those who attended and resided at Indian Residential Schools as part of a settlement of a class action brought on behalf of the survivors of those schools. However, as noted by the Federal Court in this case, “[t]heir classmates who attended the same classes, but who went home at night, received nothing”.

The plaintiffs in this class action include day students that attended the Kamloops Residential School between 1949 and 1969 or the Sechelt Residential School between as early as 1941 and 1969. Descendants of day students (many of whom have already passed away) are also named as plaintiffs, as are band members and the bands themselves on whose lands these residential schools were located.

The plaintiffs seek declarations that the federal government owed them and breached fiduciary, constitutional, statutory and common law duties in relation to the establishment, funding, operation, supervision and control of residential schools; that their Aboriginal rights were breached and the federal Indian Residential School Policy caused them cultural, linguistic and social harm; and that the federal government failed to act honourably towards them. The plaintiffs also seek reconciliation, as well as pecuniary and non-pecuniary general damages, and exemplary and punitive damages.

The plaintiffs brought a motion to have a class action certified in which all day students at some 140 schools covered by the IRSSA would be plaintiffs, along with their descendants, including those not yet born. The plaintiffs also proposed that Indian Bands whose lands had residential schools built upon them would be able to opt into this class action. The proposed class period was from 1920, when the Indian Act was amended to provide for compulsory education for “Indian” children, to 1997, when the last residential school is said to have closed.

Due in part to the complex history of the negotiation of the IRSSA, day students were not entitled to receive the “Common Experience Payment” available to students that resided at residential schools under the IRSSA, with the exception of the former day students of the Mohawk Institute Residential School in Ontario. On the other hand, day students were entitled to apply for compensation under the “Independent Assessment Process” created under the IRSSA, “provided they signed a broadly worded release”.

Court’s decision

First, the Court found that the plaintiffs’ pleadings disclosed a reasonable cause of action.

The federal government argued that it would be impossible to prove the plaintiffs’ allegation that there had been a federal policy to “solve the ‘Indian problem’ by eliminating Indians” and assimilate Indigenous people “into ‘white man’ society by the systematic erosion of their languages and cultures”. It argued that even if such a policy existed, it would not be justiciable as a matter of government policy beyond the jurisdiction of the courts. The federal government also argued that there has never been a judgment for loss of language and culture before and that the plaintiffs, as individuals, cannot assert Aboriginal rights “as a sword” due to the communal nature of these rights. Further, the federal government argued that the claims were time-barred.

In terms of the novelty of the claim, the Court held that it was not in a position to weigh the plaintiffs’ chances of success at this point. It held that a novel claim should be allowed to proceed and it noted that the novelty of a claim for loss of language and culture had not prevented other courts from certifying related class proceedings that were resolved through the IRSSA. The Court also cited a recent Federal Court of Appeal decision in support of an action based on “indefensible applications of policy”.

The Court also discussed the plaintiffs’ asserted language and cultural rights. The Court found it was not necessary to set the boundaries of these rights but stated that “[t]hese are human rights which existed long before the arrival of European settlers” and found it was not plain and obvious that the plaintiffs cannot succeed with this claim.

With respect to the argument that the claims were barred by statutes of limitations, the Court noted the uncertainty left following the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2013 decision in Manitoba Metis Federation v. Canada as to the application of limitation periods in Aboriginal rights and honour of the Crown litigation. The Court noted that it was only after Aboriginal rights were recognized in the Constitution Act, 1982 that the extent of these rights “became the subject of intense litigation” and “[t]he sui generis relationship between Canada and its Aboriginal peoples, with its fiduciary and honourable aspects, is judge-made and very fluid”. As a result, the Court found it was not plain and obvious that the claims were time-barred.

The Court had no difficulty finding an identifiable class of two or more persons in this case, with the federal government having provided estimates as to the number of survivors from the two residential schools currently at issue in the litigation and two members of the “band” class already being involved at this point. The Court was also satisfied that there were common questions of fact and law, which predominate over questions affecting only individual members, and that there would not be a significant number of potential members who have a valid interest in controlling separate proceedings. And while there were some areas of potential overlap with the matters settled through the IRSSA and releases signed by those who participated in the processes under that agreement, the Court found that it would be up to the trial judge to determine these issues. The Court also affirmed that interpretation of the IRSSA is subject to judicial review.

The Court went on to find that a class proceeding was the preferable procedure for these claims as it would be on a “no-cost basis” for litigation the outcome of which was “far from certain”; class proceedings were certified in similar actions; and class proceedings appear to be “more and more, the route preferred by the Supreme Court [of Canada]”.

In terms of classes, the Court did hold that the description of the “defendant” class, which “concurrently runs five generations or more and purportedly includes descendants not yet born,” could create “a liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class”. Based on the evidentiary difficulties posed for this class, the Court limited it to the first generation of the descendants of day school students.